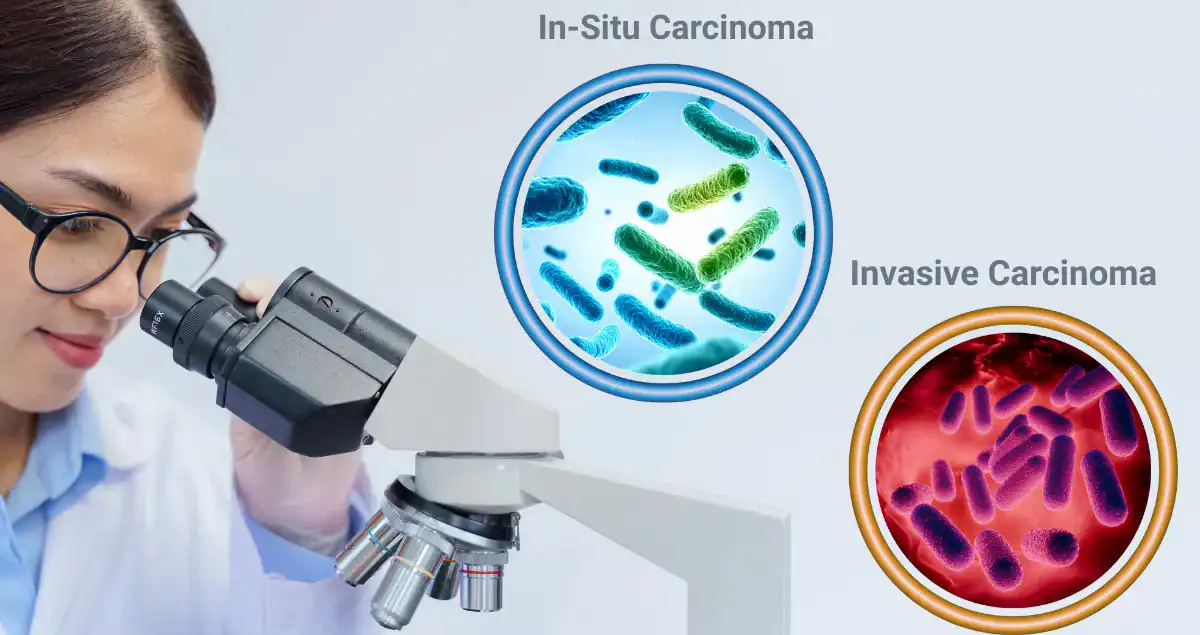

The distinction between in-situ and invasive carcinoma is one of the most important concepts in cancer pathology. Although the terms sound similar, they describe fundamentally different disease states with very different implications for treatment, prognosis, and follow-up.

This distinction is not based on tumor size or symptoms. It is determined by microscopic examination of tissue and reflects whether cancer cells have remained confined or have spread into surrounding tissue.

What In-Situ and Invasive Mean in Pathology

In pathology, the key difference between in-situ and invasive carcinoma is whether cancer cells have crossed their natural tissue boundary.

In-situ carcinoma refers to abnormal cancer cells that remain confined to the layer of tissue where they originated. They have not invaded surrounding structures or gained access to blood vessels or lymphatic channels.

Invasive carcinoma means cancer cells have breached that boundary and infiltrated nearby tissue. Once invasion occurs, the cancer has the biological potential to spread beyond its original site.

Why This Boundary Is So Important

Most cancers begin in epithelial tissue, which sits on a thin structural layer called the basement membrane. As long as cancer cells remain above this membrane, they are considered in-situ.

When cancer cells penetrate through the basement membrane, they gain access to lymphatic and blood vessels. This transition marks the point at which metastasis becomes possible and treatment strategies change.

In-Situ vs Invasive Carcinoma in Breast Cancer

In breast cancer, the most common in-situ diagnosis is ductal carcinoma in situ, often abbreviated as DCIS. In DCIS, abnormal cancer cells are confined to the milk ducts and have not invaded surrounding breast tissue.

DCIS is considered non-invasive. It cannot spread to lymph nodes or distant organs because it has not crossed the basement membrane. Treatment typically focuses on local control and reducing the risk of progression.

Invasive breast carcinoma occurs when cancer cells break out of the ducts or lobules and infiltrate surrounding breast tissue. Once invasion is present, evaluation of lymph nodes and consideration of systemic therapy may be necessary.

Pathology reports clearly state whether invasive cancer is present alone, DCIS is present alone, or both are present together, as each scenario affects treatment decisions.

Why Microinvasion Matters in Breast Cancer

Some pathology reports describe microinvasion, meaning very small areas of invasion are present. Even minimal invasion changes the diagnosis from in-situ to invasive.

This distinction matters because it may influence staging, lymph node evaluation, and treatment planning. Pathologists carefully examine breast tissue and may use special stains to confirm whether invasion has truly occurred.

In-Situ vs Invasive Carcinoma in Cervical Cancer

In the cervix, in-situ carcinoma refers to abnormal cells confined to the surface lining of the cervix. These lesions may also be described using high-grade precancerous terminology, depending on classification systems.

In-situ cervical disease has not invaded deeper cervical tissue. It is often detected through screening and can be treated before invasion occurs.

Invasive cervical carcinoma is diagnosed when cancer cells penetrate into the cervical stroma. Once invasion is present, staging expands and treatment may involve surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy.

Pathology reports in cervical cancer often emphasize the depth and extent of invasion because these features directly guide management.

In-Situ vs Invasive Carcinoma in Colon Cancer

In colon cancer, in-situ carcinoma is rare but can occur as high-grade dysplasia (HGD) within a polyp or the colonic mucosa. HGD represents abnormal cells confined to the mucosa, with no invasion into the submucosa.

Like other in-situ lesions, HGD cannot spread to lymph nodes or distant organs. However, it is considered a serious precancerous lesion because it carries a high risk of progressing to invasive colon cancer if not completely removed.

Invasive colon carcinoma is diagnosed when cancer cells extend into the submucosa or deeper layers of the bowel wall. This transition is critical because it marks the potential for metastasis and guides the need for additional therapy.

Pathology reports document the deepest level of invasion, as well as the presence of high-grade dysplasia, because both features influence treatment and follow-up.

Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PIN) and Its Relation to In-Situ Disease

In the prostate, a true in-situ carcinoma equivalent does not exist in the same way as breast or cervical tissue. Instead, pathologists may identify prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), particularly high-grade PIN.

High-grade PIN represents abnormal prostate cells confined to the prostate glands, without invasion into surrounding tissue. It is considered a precursor lesion rather than outright cancer. While it does not have metastatic potential on its own, it indicates an increased risk of developing invasive prostate cancer in the future.

Low-grade PIN is less clinically significant, but high-grade PIN often triggers closer surveillance or repeat biopsy. The key distinction mirrors the in-situ vs invasive concept: PIN is confined and pre-invasive, whereas invasive prostate cancer has broken through glandular boundaries and may infiltrate surrounding tissue.

Why Imaging Cannot Reliably Distinguish In-Situ From Invasive

Imaging studies can detect masses or abnormal areas but cannot reliably determine whether cancer cells have invaded surrounding tissue. Only microscopic examination of tissue can confirm invasion. This is why biopsy and surgical pathology are essential for accurate diagnosis and staging.

Why In-Situ or High-Grade Dysplasia Does Not Mean Harmless

Although in-situ carcinoma, high-grade dysplasia, or high-grade PIN has not spread, it is not benign. These lesions represent abnormal or precancerous changes with the potential to progress to invasive disease if left untreated.

The key difference is that these lesions are often detected earlier and treated more conservatively, with excellent outcomes when managed appropriately.

Why Invasive Does Not Mean Untreatable

The term invasive can sound alarming, but it does not define prognosis on its own. Many invasive cancers are detected at an early stage and are highly treatable.

Invasion describes location and behavior, not outcome. Other factors such as grade, stage, biomarkers, and response to treatment play equally important roles.

How Pathologists Determine Invasion

Pathologists evaluate tissue structure, cellular arrangement, and the presence or absence of supporting layers. Special stains may be used to highlight structural boundaries that disappear when invasion occurs.

This careful assessment ensures accurate classification and appropriate treatment planning.

Why This Distinction Drives Treatment Decisions

Whether a cancer is in-situ, a precursor lesion like high-grade dysplasia or high-grade PIN, or invasive influences decisions about surgery, lymph node evaluation, systemic therapy, and long-term surveillance.

A single word or phrase in a pathology report can explain why treatment recommendations differ significantly between patients.

Final Thoughts on In-Situ, Invasive Carcinoma, HGD, and PIN

The difference between in-situ and invasive carcinoma and the presence of precursor lesions like high-grade dysplasia in the colon or high-grade PIN in the prostate defines whether abnormal cells remain confined or have begun interacting with surrounding tissue.

Understanding this distinction in breast, cervical, colon, and prostate tissue helps patients interpret pathology reports, understand risk, and engage meaningfully in treatment decisions. Pathology does more than name disease it explains its behavior, which shapes every next step in care.