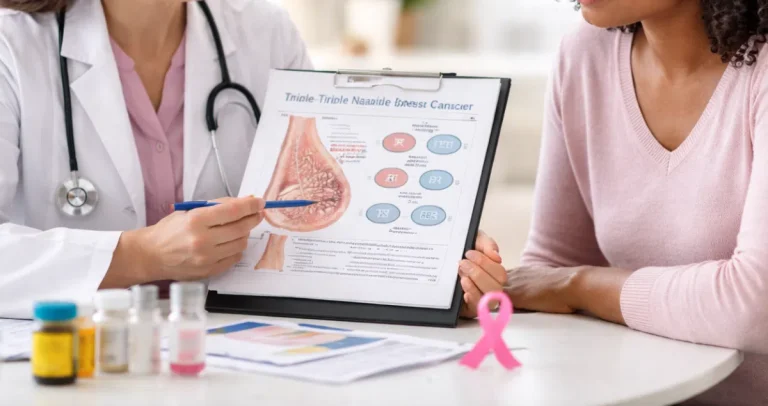

Advances in molecular pathology have revolutionized cancer diagnosis and treatment. Genetic mutations within cancer cells can provide critical information about tumor behavior, prognosis, and the most effective therapies. Pathologists play a key role in testing for these mutations, integrating molecular findings with traditional tissue analysis to provide comprehensive insights. Understanding how these tests work helps patients interpret results, participate in treatment decisions, and feel confident in their care.

Why Genetic Testing Is Important in Cancer

Genetic testing of tumors identifies mutations that drive cancer growth. These mutations can affect how aggressive a tumor is, how likely it is to respond to certain treatments, and whether targeted therapies or clinical trials may be appropriate. For example, testing a lung tumor for an EGFR mutation may indicate that a patient could benefit from a targeted therapy rather than standard chemotherapy. Similarly, BRCA mutations in breast or ovarian cancers may inform treatment decisions and identify risks for family members.

Pathologists ensure that these tests are performed accurately and interpreted in the context of the tumor type, stage, and overall patient health. Honest Pathology principles highlight transparency in reporting, helping patients understand not just the mutation itself, but its clinical significance.

How Tumor Samples Are Collected

Testing for genetic mutations begins with obtaining a sample of the tumor. This can be from a surgical resection, core needle biopsy, or sometimes a liquid biopsy using circulating tumor DNA from the blood. Once collected, the sample is sent to the pathology lab for preparation.

The tissue is usually preserved in formalin and embedded in paraffin to maintain its cellular structure. Pathologists examine the tissue under the microscope to confirm that tumor cells are present and select areas most suitable for molecular testing. Ensuring that the sample contains sufficient tumor material is critical for accurate results.

Techniques Pathologists Use for Genetic Testing

Several techniques are used to detect genetic mutations in cancer. One common method is polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which amplifies specific DNA sequences to identify known mutations. Another approach is next-generation sequencing (NGS), which allows comprehensive analysis of multiple genes simultaneously. NGS can detect point mutations, insertions, deletions, and copy number changes across dozens or hundreds of genes.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is another tool used to detect specific gene rearrangements or amplifications, such as the HER2 amplification in breast cancer. Immunohistochemistry may also be employed to detect abnormal protein expression that correlates with underlying genetic changes. In some cases, pathologists use liquid biopsies to detect tumor DNA fragments circulating in the blood, offering a non-invasive option for monitoring mutations over time.

Interpreting the Results

Once the genetic testing is complete, pathologists interpret the findings in the context of the patient’s tumor type and clinical situation. A mutation may be classified as pathogenic, meaning it drives cancer growth; likely pathogenic; or of uncertain significance, indicating that its impact on tumor behavior is unclear.

For example, in colorectal cancer, detection of a KRAS mutation may indicate that certain targeted therapies will not be effective, while the absence of a mutation may open up additional treatment options. In breast cancer, HER2 amplification identified by FISH can indicate eligibility for HER2-targeted therapy. Honest Pathology principles emphasize clarity, helping patients understand the implications of mutations without unnecessary technical confusion.

Impact on Treatment Decisions

Genetic mutation testing has a direct influence on treatment planning. Targeted therapies are designed to act on specific mutations, often with higher effectiveness and fewer side effects than traditional chemotherapy. Testing can also identify eligibility for clinical trials evaluating novel therapies.

For instance, a lung cancer patient with an ALK rearrangement may be treated with an ALK inhibitor, which specifically targets the abnormal protein produced by the rearranged gene. Patients with mismatch repair deficiency or high microsatellite instability may be candidates for immunotherapy. By explaining these options clearly, pathologists help physicians and patients choose the most appropriate, personalized treatment strategy.

Understanding Limitations of Genetic Testing

While genetic testing is powerful, it has limitations. Not all mutations are clinically actionable, and some may be rare or of uncertain significance. Tests may not detect all mutations, especially if the tumor sample is small or contains few cancer cells. Additionally, a mutation found in one part of a tumor may not be present throughout the entire tumor due to heterogeneity.

Pathologists play a key role in contextualizing these results, explaining what the findings mean for treatment options, prognosis, and follow-up. Honest Pathology principles encourage transparency about both what the test can and cannot tell patients, helping set realistic expectations.

Communicating Results to Patients

Genetic testing results are often communicated to patients through the treating oncologist, sometimes with direct consultation with a pathologist. The pathologist’s report describes the mutation, explains its clinical significance, and may suggest further testing or monitoring if needed. Patients can benefit from asking questions such as: how does this mutation affect treatment options, what does it mean for prognosis, and are there lifestyle or family considerations?

Clear explanations help patients make informed decisions, reduce anxiety, and empower them to participate actively in their care. Pathologists, guided by Honest Pathology principles, strive to make complex molecular information understandable and actionable.

Follow-Up and Monitoring

Genetic testing can also guide monitoring over time. Some mutations may emerge or change during treatment, and repeat testing can help adjust therapy accordingly. Liquid biopsies offer a way to track tumor DNA non-invasively, while tissue biopsies can provide detailed information about new or resistant tumor clones. Understanding the dynamic nature of mutations helps patients and physicians adapt treatment plans as needed.

Conclusion

Testing for genetic mutations in cancer is a crucial part of modern oncology. Pathologists play a central role in selecting appropriate tumor samples, performing sophisticated molecular tests, and interpreting results in the context of clinical care. These findings guide treatment decisions, eligibility for targeted therapies or clinical trials, and ongoing monitoring. Honest Pathology principles ensure that results are communicated transparently and clearly, helping patients understand the significance of their mutations and participate confidently in their care.

By combining microscopic tissue analysis with molecular testing, pathologists provide a comprehensive picture of the tumor, supporting personalized, effective treatment strategies and empowering patients with clear information about their cancer journey.