Infections can affect any part of the body, from the skin and lungs to the digestive tract and internal organs. While symptoms such as fever, pain, or swelling can suggest infection, tissue analysis often provides the clearest and most definitive diagnosis. Pathologists examine tissue samples under the microscope to identify bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, and to assess their impact on the surrounding tissue. Understanding this process helps patients interpret their results and engage in their care.

Why Tissue Analysis Matters

Blood tests, imaging, and cultures can suggest infection but sometimes miss localized or subtle infections. Tissue analysis allows pathologists to directly observe the infection and evaluate its effects on nearby cells. For instance, a lung biopsy may reveal bacterial pneumonia even if blood cultures are negative, and a gastrointestinal biopsy can detect a viral infection that stool tests miss.

Clear and honest communication of these findings, such as the explanations provided by resources like Honest Pathology, ensures patients understand what the report actually shows, reducing uncertainty and confusion.

How Samples Are Collected

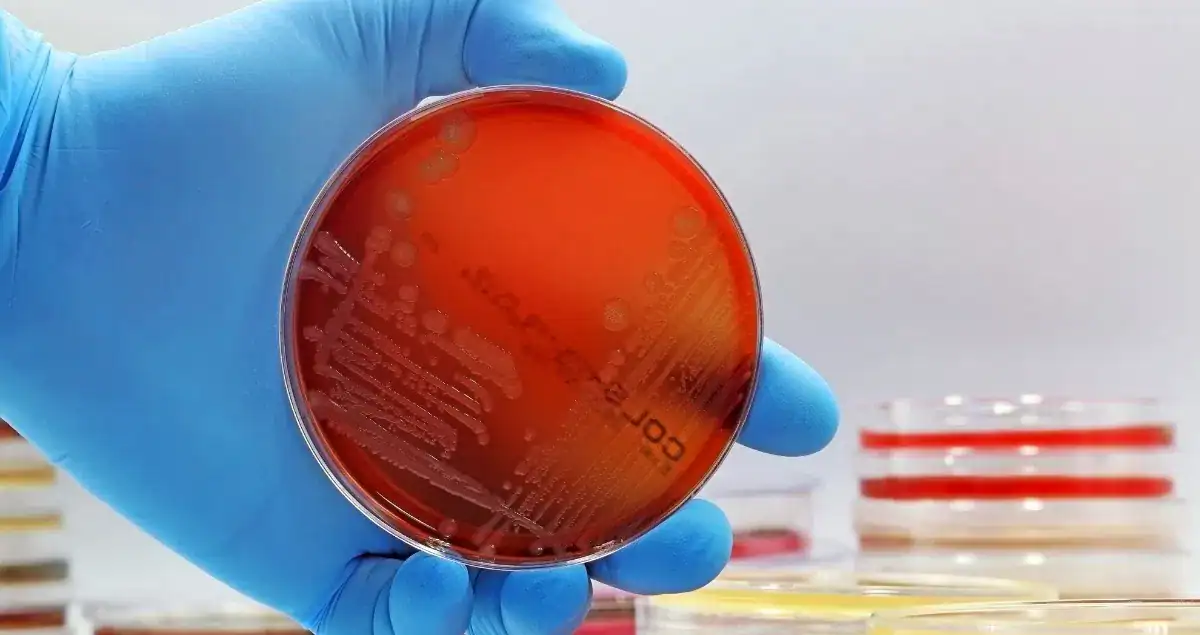

Tissue samples are usually collected via biopsy or surgical procedures. A skin lesion may be biopsied to check for bacterial or fungal infection, while a liver biopsy can identify viral hepatitis. During collection, a small piece of tissue is preserved, processed, and prepared for microscopic examination.

Pathologists use special stains to highlight microorganisms and immune responses. For example, an acid-fast stain may detect tuberculosis bacteria, and a periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain highlights fungal organisms. These techniques allow for precise identification of pathogens that may not be visible with routine staining.

Microscopic Examination

Under the microscope, pathologists examine tissue structure, cell types, and any microorganisms present. Infected tissue typically shows inflammation, including immune cells such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, or macrophages. The pattern of these cells can suggest the type of infection: neutrophils are common in bacterial infections, while lymphocytes may indicate viral infection.

Pathologists also search for the infectious organisms themselves. Helicobacter pylori, for example, can be seen in the stomach lining using a silver stain, while Candida appears as characteristic yeast structures under PAS stain. Even low numbers of microorganisms can confirm a diagnosis.

Honest Pathology emphasizes transparency in reports, helping patients understand what is being seen under the microscope and what it means for their health.

Types of Infections Identified

Tissue analysis can reveal a variety of infections. Bacterial infections may include tuberculosis in the lungs, skin abscesses, or infected heart valves. Viral infections can appear in the liver, such as hepatitis B or C, or in the skin and mucous membranes. Fungal infections, like aspergillosis in the lungs or Candida in the gastrointestinal tract, have distinct appearances in tissue. Parasitic infections, such as Giardia in intestinal biopsies, can also be confirmed microscopically.

Reports often describe tissue damage caused by the infection, including necrosis, scarring, or chronic inflammation. Understanding the extent of infection and tissue involvement guides treatment decisions.

Additional Testing Techniques

When microorganisms are difficult to see, pathologists may use advanced techniques. Immunohistochemistry employs antibodies that bind to specific microbes, making them visible. Molecular tests, such as PCR, can detect DNA or RNA from bacteria, viruses, or parasites, even when only a few organisms are present.

These methods complement routine microscopy and special stains, ensuring a thorough evaluation of the sample. Honest Pathology encourages clear explanations of these advanced tests so patients can understand why they might be needed and what their results mean.

Interpreting the Report

Pathology reports typically include a gross description, microscopic description, and final diagnosis. The gross description notes tissue appearance before microscopic evaluation, such as discoloration, swelling, or ulceration. The microscopic description details immune cells, inflammation patterns, and any microorganisms seen. The final diagnosis names the infectious agent when identifiable and may suggest additional testing or treatment.

For example, a report might read: “Acute suppurative inflammation with Gram-positive cocci consistent with Staphylococcus infection.” Another example: “Chronic hepatitis with viral inclusions consistent with hepatitis B virus.” These descriptions clarify both the type of infection and its impact on tissue.

Common Questions Patients Have

When reviewing pathology results, patients often want to know what type of infection is present, whether it is acute or chronic, and how severe it is. They may also ask what treatment is recommended. A skin biopsy showing fungal hyphae might require oral antifungal medication, while a lung biopsy confirming tuberculosis leads to a specific multi-drug regimen. Honest Pathology supports clear communication so that patients can understand both the diagnosis and the rationale behind treatment decisions.

Conclusion

Pathologists play a critical role in diagnosing infections by examining tissue samples under the microscope. Using stains, immunohistochemistry, and molecular techniques, they can identify bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites while assessing tissue damage and inflammation. Reports provide detailed, transparent information about the infection, which informs treatment decisions and follow-up care. Resources like Honest Pathology help ensure patients receive clear explanations, making it easier to understand what the findings mean for their health.